I’ve said it until I’m blue in the face, but writing women characters well in videogames does not mean making them pure paragons of perfect morality. Indeed, it often means the very opposite, as the case of Dragon Age’s Empress Celene Valmont and Ambassador Briala illustrates in deeply sanguine colours.

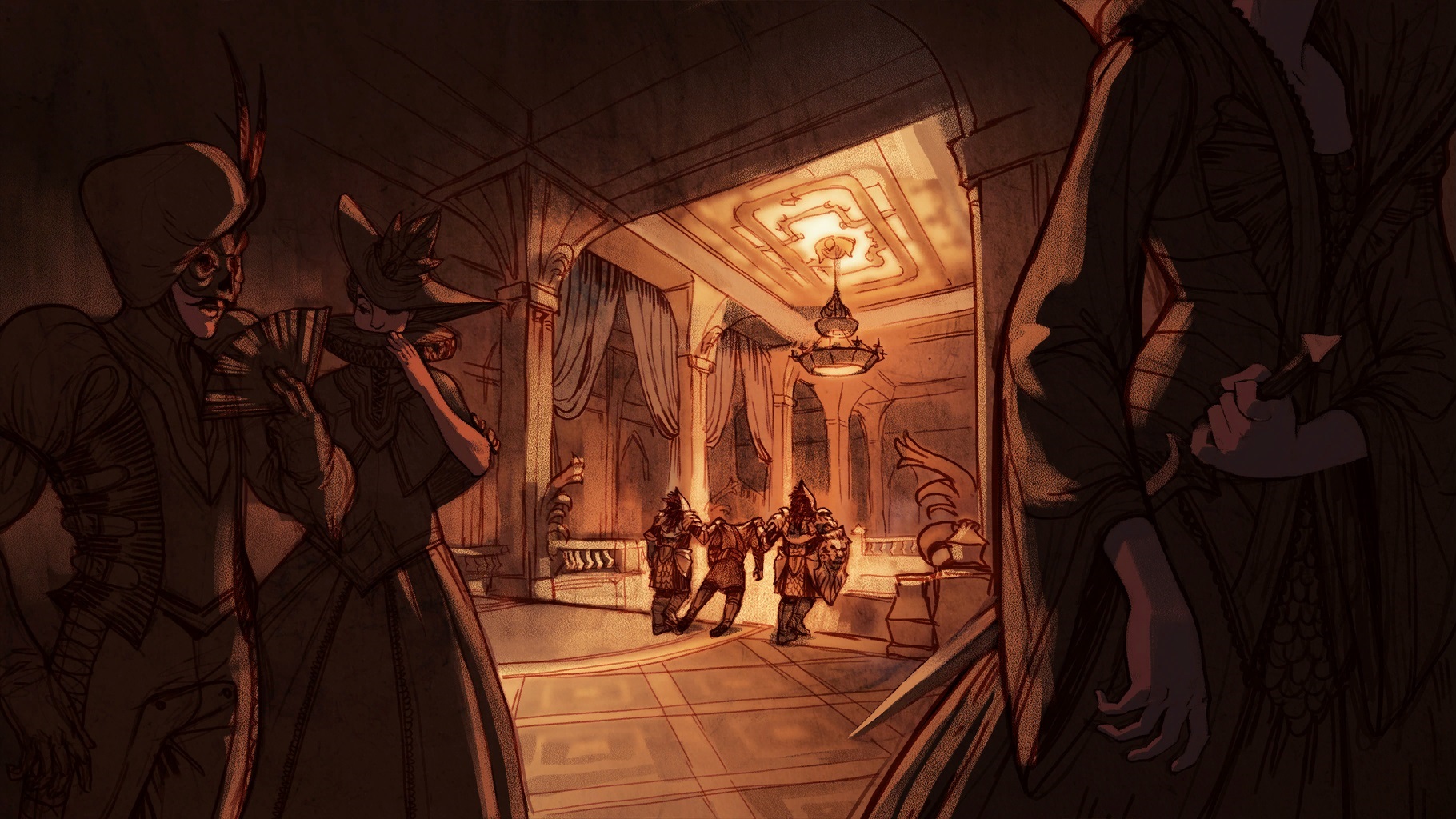

Dragon Age: Inquisition’s aptly named main quest, “Wicked Eyes, Wicked Hearts,” sees your character visit the Orlesian Imperial Winter Palace in a bid to stop an assassination attempt on Empress Celene I, to thwart the plans of the game’s antagonist and prevent Thedas’ most powerful nation from sliding into chaos.

Here you dive into a well-designed thicket of political intrigue at a masquerade ball-cum-peace conference between Celene and her foe in the Orlesian Civil War, Grand Duke Gaspard, who seeks the throne for himself. A third party is also triangulating at the ball from the perch of a grand balcony, Ambassador Briala who speaks for the Elven rebels who had been harrying both sides in the civil war.

Yet so much more is going on behind all these wicked eyes, as you quickly learn that Briala and the Empress have no small amount of history.

***

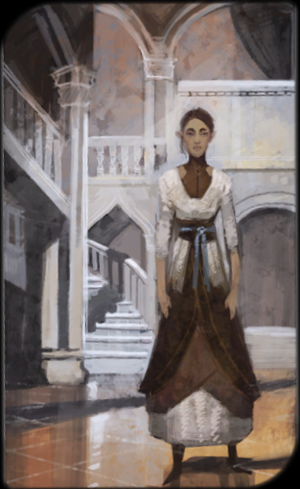

Briala was once Empress Celene’s personal chambermaid, who acted as her eyes and ears–and even her blade– in the palace, in the slums of Val Royeaux, and further afield when it was required. As you collect rumours and gossip from the prattling guests at the Winter Palace, you also learn that she and Celene were once lovers. In your explorations of the off-limits parts of the palace you can find a storeroom where Celene has kept an Elven locket and use it to confront both Celene and Briala with the rumour, to which they both admit (why hide such a thing from someone called ‘the Inquisitor,’ after all?).

Orlesian custom is a spiderweb of decorum, metaphor, and implication, and I realised this when both women discussed how they “parted ways” in very gentle, almost unassuming terms. Celene says that Briala “wanted change [for the Elves], and thought I should be the one to deliver it.” Even though she expresses regret and says she should’ve “dared more,” she steels herself beneath her mask and insists the locket meant nothing to her. Briala, for her part, is shocked that Celene kept the token, which she had long ago gifted to Celene in honour of her coronation, but her thoughts immediately turned to how impolitic and un-strategic it was for her to keep it.

That Orlesian understatement, however, hints at something far greater and far darker.

***

Bioware writer Patrick Weekes tried his hand at writing a Dragon Age novel, the first penned by someone other than David Gaider, and acquitted himself mightily with “The Masked Empire,” the backstory behind everything that came to a head in “Wicked Eyes and Wicked Hearts.” In the process he provides a blueprint for writing queer women as believable, flawed, and troubled people.

This book is where it all began, over a year earlier: the civil war, the Elven rebellion, Gaspard’s ascendancy, and Celene and Briala’s breakup. Briala herself is brilliantly portrayed as a permanently compromised woman: an Elf with the ear of an Empress, using her not inconsiderable influence to steadily improve the lot of her people in a kingdom that despises and ghettoises them.

Every day she lives with the conflict of knowing she is an Elf, and at once more powerful than most of her people, yet still subject to the Empress’ whim. She knows the alienage of Val Royeaux well, yet stands as a woman apart from its residents, better dressed and infinitely more privileged from them, above their quotidian struggles. Neither is she of the purist, nationalist ideology that pervades the Dalish clans who roam the countryside, trying to live in accordance with an ancient culture that humans long ago destroyed.

Despite it all, and despite all the rumours and sniping from the shadows, she strives to use her position to improve the lives of Elves–getting them admitted to Thedas’ Oxford, the University of Orlais, for instance, or allowing Elven merchants to sell wares outside the slums and alienages to which Elves are normally confined. This life of compromise, of being the outsider insider who runs between worlds and belongs nowhere, is a brilliant picture of what it means to be a relatively privileged and fortunate member of an otherwise marginalised group–forever caught between the conservative tendencies of power, and the radical will of the oppressed who want (and need) change right now.

Celene, meanwhile, is the perfect portrait of the moderate liberal, whose desire for progressive change is sincere but mired under layers of old prejudices and imperial disdain for those she sees as beneath her; Briala knows that as much as they love each other, Celene still sometimes sees Briala as “one of the good ones,” a thought that guts her.

I won’t summarise all the events of the book, and instead rush to spoil the main bits. Due to political manoeuvring gone awry, Celene violently puts down an Elven rebellion in the city of Halamshiral murdering hundreds or even thousands of Elves, just as Briala was attempting a more subtle, targeted solution that might have calmed everyone down. Celene justified this as an unavoidable response to the Elven rebellion, and a necessary evil that would prove her tough enough to keep the throne and making small, incremental change. Despite herself, over the course of a long journey through the wilderness, Briala seems to forgive Celene and commits herself to getting her love back to Val Royeaux where she can reclaim her throne after an ambush by Gaspard drove her into temporary exile.

Later in the book, Celene’s champion, Michel, duels Gaspard honourably for the throne of Orlais; Gaspard loses and bares his neck to the blade of his opponent. In that precise moment, Briala calls in a favour that Michel owed her. The favour? Yield and allow Gaspard to live. For those who played Inquisition, the ramifications of that decision are clear.

Had Gaspard died, there would have been no civil war; a throne war requires a usurper, after all, and Gaspard’s cult of personality drove the revolt against Celene’s supposedly weak and effete rule. Instead, Briala took away the very thing that mattered most to Celene: the stability of her empire. She lit a fire before Celene and walked away from her, the palace staff, and her old life in Val Royeaux. Both women were heartbroken, but Briala did what she needed to, even after she and Celene had burnt down a Dalish village where they were being held prisoner. Briala did it both because she had lost faith in the Dalish, who she now saw as the enemies of her people in Thedas’ alienages for their aloof scorn of their ‘flat eared’ kin, and to help Celene. Celene did it for herself, to make her escape back to Orlais proper–only for Briala to stop it all and give her benediction to a civil war that took away nearly everything Celene wanted, including the love of her life.

The blood on both women’s hands is undeniable and without measure, each chasing after a distant moral goal and ruthlessly compromising whatever it took to reach it, convinced that they alone knew what was best for the millions who milled in the world beneath them.

Two of a Kind

“Sitting on my throne, I see every city in the empire. If I must burn one to save the rest, I will weep, but I will light the torch!”

~Empress Celene, The Masked Empire

Briala became a revolutionary for her people, but could never quite admit to herself that she saw “little people” in much the same way as Celene: chess pieces to be moved in a grand game with grander goals. Neither, of course, expected the chess pieces to understand their motivations. Briala and Celene both were convinced that their actions, however violent, were in the ultimate service of a better society–and indeed they were hemmed into that terrifying calculus by the very brutality of Thedas itself, a murderous world where one lives and dies by the sword, and where Elves are treated like game animals by humans; Briala knew some compromise was necessary.

Such compromise would cost her in the eyes of some of her own people, including those she sacrificed so much to help. In Inquisition, you can find an Elven servant who despises Briala. “Now she wants to play revolution. But I remember. She was sleeping with the empress who purged our alienage,” she seethes, scorning her as “Celene’s pet.”

Briala and Celene, despite existing at opposite ends of a power spectrum, were more alike than either cared to admit. It is telling that Briala’s act of vengeance against Celene for Halamshiral was political rather than something purely personal. She met Celene’s burning slum and raised her a burning empire.

It was a terrifying, bloody dance that only these two women in love could perform. If you bring Sera along with you to the Winter Palace, upon meeting the bitter servant and hearing her confirm Briala and Celene were lovers, she remarks “Knew it! I did. And I bet the hate made it feel real good.” She’s perhaps more right than she knows.

Briala was resented as a ‘flat-eared’ Elf by some, seen as a ‘knife ear’ by humans, and too privileged to understand the alienages by others. She preached the gospel of compromise even as she struggled with terrible existential questions. How far do you “sell out” before the bad outweighs the good? What is worth sacrificing now for gains down the road? When do you fight prejudice and when do you grin and bear it?

Celene, meanwhile, compromised from the other direction: how radical could she be without ceding the very power she needed to enact change? How many nobles could she turn against her while still saving lives? One is left to wonder how much of this terrible conflict both women worked out upon each other.

The Perfect Videogame Protagonists

Briala’s mother framed the mother of another servant girl in the palace to position her daughter beside the young princess who would be queen. Her whole life was a series of dances in Orlais’ deadly Game, the often deadly political intrigues that serve as an unintentional metaphor for videogaming if ever there was one. Celene and Briala are both the stars of their own stories, with everyone else, even each other at times, a supporting character to be set alight if expediency to the win condition demands it. They’re the ultimate videogame protagonists in that way–your Inquisitor, who already cut a bloody swathe through Thedas by the time “Wicked Eyes, Wicked Hearts” begins, is no different. But Celene and Briala’s tortured love for one another provides an especially twisted reflection through which to understand this phenomenon.

Where did the revenge end and the revolution begin, for Briala? After she let Gaspard live, after all, she took over a network of eluvians (ancient Elven mirrors that allow for instant travel over vast distances), inaugurating a spy network and rebellion that actively prolonged the bloody civil war Briala started. All this in the name of creating space to help the Elves of Orlais’ slums and alienages. It’s hard not to wonder if Celene wouldn’t have been proud behind her anguish. Both women, after all, saw the world from ten thousand feet; both were master strategists who were not above sacrificing what they saw as pawns on a grand board.

At the end of “Wicked Eyes” your Inquisitor can choose to reunite Briala and Celene, while Gaspard is finally put to the sword that Briala had mercifully spared him from a year earlier.

In that event, Celene keeps her throne, and Briala becomes the Marquise of the Dales, the first Elf to hold a noble title in Orlais. Fitting that it should occur in Halamshiral, where the two lovers set both their lives aflame not long ago; the only way they could truly reconcile was through a night of deadly political manoeuvres that saw everyone from nobles to Tevinter mages to servants die in the palace’s gilded halls, a bloody game that both women knew could end with one or both of them losing for the last time.

As they give their victory speech, the gathered nobility listen while Celene talks about the “cornerstone of change” being laid, and Briala speaks rousingly of how the night’s events are a “triumph for everyone,” in keeping with the way Elves and humans alike fought against the ancient Tevinter Imperium centuries ago. Pitch perfect politics, and Briala reveals herself as every inch the equal of Celene, even when delivering an historic speech for the benefit of the entire nation.

What the crowd did not see was the blood that trailed behind both women as they held hands in the dark.