***

Spoilers for Mass Effect: Andromeda

Note: For ease of reference I refer to the player character as Sara Ryder, but if you played as Scott because you’re into that sort of thing, feel free to substitute as you read.

Mass Effect: Andromeda is unjustly maligned. It’s surprisingly fun and lovable for a game that earned the searing hatred of fans and critics alike, proving with depressing conclusiveness that there’s no space for flawed gems in the world of gaming.

But flawed it certainly was, and perhaps the ugliest carbon crystal in this gem is your character’s dear old dad Alec Ryder, who dies in the prologue and lives on as a malingering digital spectre. In a bit of accidental horror, you feel yourself steadily being driven mad by the fact that you’re the only person who thinks that a man built up by the narrative to be a hero is, in fact, evil.

***

In her review of Frozen 2 YouTuber Jenny Nicholson described the film as having “good bones but no skeleton.” In the same vein one can say Mass Effect: Andromeda has good bones but no spine.

The game suffers from a few problems, especially in its first act. Here, poor pacing, anaemic voice acting from core characters, and (at least at launch) janky animations conspired to give players a first impression the game never recovered from. By the time you build your first colony on Eos, however, everything starts to come together: your crew, the more interesting parts of the main story, and your sense of the game’s rhythms.

But Alec Ryder is the game’s shattered spine, whose failings run through the game from top to bottom. It all deals a near-crippling blow to the characterisation that is otherwise ME:A’s strength. This happens because the story of Ryder’s family is clearly set up to be her story’s emotional core, and it is mechanically structured to be the narrative throughline linking the entire game together in the background.

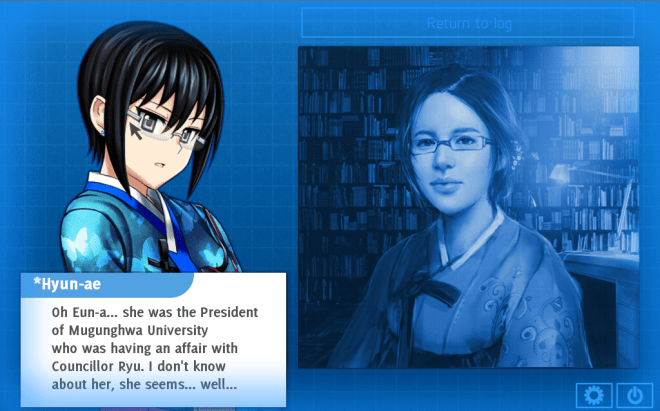

In brief: your AI, SAM, is literally in your head thanks to an implant. It’s a special tool used by every Pathfinder, and when your father bites it in the game’s prologue, he quickly transfers his SAM to your implant, making you his successor as human Pathfinder. But! Drama! You learn that you have access to some of your father’s memories and that they are locked. As you ‘grow’ as a Pathfinder (i.e. explore the Heleus Cluster and level up) these memories return and reveal dark secrets about your father, your family, and the entire Andromeda Initiative.

Or at least, that’s what the game gives the impression of. It largely fails to deliver on this because, despite literally getting to be inside Alec Ryder’s head, you learn nothing meaningful about his character, his inner life. This wastes a narrative opportunity provided by the SAM implant: the chance for Ryder to deepen her relationship with her father even though he’s already dead, and for us to go along for an emotionally impactful ride.

Why does this happen? In large measure because his story is bled dry of meaningful conflict. Alec Ryder makes numerous questionable choices (to put it politely) and yet is still treated as a straightforward hero by the game and, inexplicably, by his two children who, we’re told, had a vexed relationship with him. You can only judge Alec Ryder by his actions, which portray him as a manipulative monster that the galaxy is better off without—except, bizarrely, no one responds to him as such.

So what were Alec’s sins?

Dub-Con Cryo

The grand culmination of the Ryder Family Secrets questline is the revelation that Ryder’s mum, Ellen Ryder, is alive. She’s in Andromeda and cryogenically frozen. Alec Ryder snuck her onto the human ark under a false identity, freezing her when she was on the edge of death from her terminal illness.

This is pitched to the player as a beautiful tear-jerker moment. If this were a movie, the music would swell as Sara Ryder ran through the rows of cryo pods to find the one where her mother’s face would stare back at her.

The problem is that a moment’s thought reveals the scenario as nightmarish.

You see, from Sara’s reflections and the flashbacks she gets from her father’s memories, you’re given the clear impression that Ellen Ryder was a strong-willed woman who had—in addition to a life filled with many professional accomplishments—made peace with her untimely demise. It was a tremendous act of will for her to accept that she was going to die from her illness and that comes through quite clearly in the story. It’s a triumph of personal strength by any measure.

And yet without asking, Alec both took that away from her and brought her to another freaking galaxy. The game makes clear that Alec froze Ellen without her knowing, in the hopes that a cure for her disease would be developed while she was cryogenically frozen.

Nothing in the game suggests that Ellen got to make either of these monumental decisions for herself. Beyond that, bringing her is irresponsible. The Initiative is essentially restarting civilisation in a distant galaxy; it’s a hard life, as the game makes clear. Is it one that Ellen would want to live? We don’t know. In theory, the revelation that she was dragooned into cryo is supposed to be a happy one because she’ll get to see her children again. But what if a cure for her disease isn’t found during Sara and Scott’s lifetimes? What if they’re dead by the time she can be safely released? Is her pod using resources that are better directed elsewhere? Can curing this rare disease be a priority for the limited research capacity of the Initiative?

Just thinking about being in Ellen’s shoes makes me feel ill. Yet her predicament isn’t even the core of the problem here. The core of the problem is that no one else in the game’s world seems to recognise the shittiness of Ellen’s situation. Scott has a quick line about wanting to punch his father, but it’s quickly glossed over by treacly gratitude. You’re given no dialogue options that veer from this script.

If Ellen were my mother, I’d have feelings. First, because my father lied to me about my mother dying. Second, I’d be angry that he so egregiously violated her final wishes. Third, yes, some great part of me would be relieved and grateful that I might be able to see her again. Fourth, I’d wonder if I’d live long enough to see it happen. Fifth, I’d be furious at dad once more because he gated this essential knowledge about my own mother behind a near-impenetrable AI puzzle-box that can only be unlocked by parkouring across alien worlds while being shot at constantly. Sixth, I’d feel guilty that some part of me felt grateful she was in Andromeda.

All that anguish and grief is the stuff good drama is made of. And not one whit of it plays out on screen in ME:A, despite Alec Ryder effectively being the villain from Saw.

Yet, somehow, it gets worse.

“See the Process Through”

“See the Process Through”

Throughout the first half of the game, you must struggle against widespread scorn—including from members of your own team—because Alec Ryder made you his successor as Pathfinder. You’re portrayed as kind of a dork, still trying to figure out her place in the galaxy, and nowhere near being the hotshot spec-ops Indiana Jones your father was. So, it’s an essential part of your story that you do, in fact, prove yourself worthy of being Pathfinder, even as you wonder why you’ve been chosen for this daunting task. Surely it wasn’t just sheer nepotism?

Well, it turns out that at the end of the Family Secrets quest chain, your father also tells you that Ellen’s cryogenic freezing is the whole reason chose you to be the next Pathfinder. Because you would “see the process through.” The “process” being getting Ellen out of cryo when the time was right. So, dear old dad made you the Pathfinder not because he believed in you, but because he needed to keep this shitty secret in the family, endangering you and the entire mission. Good thing you vastly exceed your father’s expectations!

It’s quite grievous. It was also unnecessary. The scene where Alec Ryder dies is one where his death was clearly accidental, sudden, and unexpected; he sacrifices himself to save you because your helmet shattered open on a planet with a toxic atmosphere, essentially. This is, perhaps, the one truly noble thing he ever does. But it’s also not exactly premeditated, nor was the fact that your sibling’s pod malfunctioned, thus side-lining him from the mission.

Alec had no way of effectively planning this, so saying that there was some grand scheme involved in making you the next Pathfinder was both needless and makes him look like an even bigger asshole.

Family

His one clear motivation in all of this was that he built the SAM AI in a galaxy that scorned artificial intelligence because he wanted to use it to save Ellen’s life. This is cliché at best and it’s given no further depth in any part of the story, despite his AI literally being a tool that could provide that depth in a seamless, narratively coherent and thematic way. After all, how many of us wish we knew why our parents are the way they are? Imagine if an implant gave you access to your parents’ thoughts; it’d be horrifying, but at least you would have real insight that offered the hope of closure. ME:A does nothing with this conceit, leaving us instead with the actions of a man who seemed to think the universe revolved around him.

It’s not hard to imagine what could’ve been.

Throughout the story of ME:A, Sara and the crew of the Tempest learn to work together and trust each other despite some well-developed conflicts and tensions that emerge along the way. In keeping with the theme of the entire Mass Effect series the crew becomes akin to a family. But for the first time in Mass Effect your character’s blood relations play a huge role in the story. They remain an active presence in your life. The player character is, thus, torn between these two worlds: her family-by-blood and her family-by-bond. That tension could have been made more central and explicit; Alec Ryder’s “family first” attitude could’ve been drawn into relief as the selfish cynicism that it really was.

It would have been tremendously satisfying for Sara to grieve the loss of her father and the loss of any hope that he would ever become a better person, to feel lost without the anchor of the Ryder patriarch before realising she never needed that in order to find true family. Despite all the talks you can have with Lexi about the Family Secrets quest chain in her role as ship psychologist there’s not much meat there. But there could’ve been: mourning and making peace with what a terrible person your father was, and what he did to you, what he’s still doing to you via his ghost that lives on in your head.

Anger turns to resolve as you accept what’s happened to your mother and vow to take care of her as best you can when she awakes. And then you turn to your crew—a real family, at last, made up of people who love you unconditionally, who will always have your back.

They emerge as a crew that serves as a reminder that family doesn’t have to be the hell created by your father, that you can carry on with your brother and your mum, but with the addition of new love and lifelong friendships, having won the admiration of thousands for being a leader and ten times the Pathfinder your father ever was.

That contrast was waiting to be drawn, yet somehow squandered. Of all the missed opportunities in ME:A this is surely the greatest.

This article was made possible by the generous support of my Patreon patrons. Why not join them?

Special thanks goes to: Ellen Anders, Quirk G., Rose H., Jamie Klouse, Miguel C., Anastasia S., Noah Caldwell, Jules, and Chris Morris, for their continued, generous support.